The news last month that Germany’s GDP had risen 1.9% in 2016 and its public sector surplus of €6.2 billion had enabled it for the third straight year to avoid borrowing on the markets merely served to reinforce the country’s reputation as the economic powerhouse of Europe.

The turnaround

Indeed, the country’s days as the sick man of the continent at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s are but a distant memory. Today, it is a given the German economic machine is one of unparalleled effectiveness, viewed from afar as effortlessly bucking the trend of manufacturing decline that is decried by economic nationalists across the West.

But as a working paper by France Stratégie economist Rémi Lallement shows, things are not all as they seem in Europe’s largest economy.

Germany has undeniably been successful over the past 15 years at creating jobs and fostering a climate of social dialogue to further lower unemployment. The proof lies in the fact it now has the lowest jobless rate it has had since reunification in 1990. In 2016 alone its economy created more than 500 000 jobs.

Fiscal consolidation has also been one of its strong suits. One of the reasons it was able to weather the financial crisis so well was that it balanced its budget in 2007 and 2008, allowing it to run a deficit and fiscal stimulus in 2009 and 2010 with little consequence. And after three years of deficits – peaking at 4.2% in 2010 – it brought its books back out of the red by 2012 and even managed to clear a surplus from 2014 to 2016.

The flip side

But Lallement points out both these achievements have come at the expense of almost no growth in real average wages from 2000 to 2013. According to the WSI Institute of Economic and Social Research in Düsseldorf, it was not until 2014 that real wages exceeded the level they had reached in 2000. It’s clear this has been an important economic adjustment variable for Germany industry.

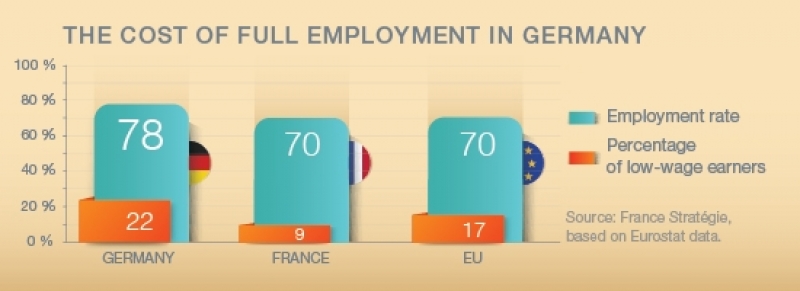

Given this, it is perhaps not surprising the country had one of the highest percentages of low-wage workers in the EU in 2014: at 22%, it was slightly higher than for the UK and more than twice that of France, which had a rate of 9% (the eurozone average was just over 17%). What’s more, their cohort has grown since 2006.

On top of this, the relative poverty rate after taxes and transfers got noticeably worse from 2005 to 2014, rising to 16.7% from 12.2% (France’s has remained relatively stable at around 13.0%).

Despite these developments, income inequality remains less than the OECD average, largely thanks to a still effective welfare state.

Spending for tomorrow

The question Germany’s neighbours – and first and foremost, its largest, France – are asking themselves today is what the country will do with the growth dividend that has come from its strong industry, high employment and rising wages.

The finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, seems set on maintaining the balanced budget policy and continuing to pay down the country’s debt to reach the debt-to-GDP ratio ceiling of 60%, as laid out in the Growth and Stability Pact (GSP), by the end of the decade.

“The government argues it doesn’t need to adopt a policy of fiscal stimulus because its economy is doing well and unemployment is low,” says Lallement. “On the contrary, Schäuble feels Germany’s current policy of consolidation is both appropriate given the current economic climate and consistent with Keynesian countercyclical fiscal policies.”

But its neighbours feel differently. They feel Germany should use its budget surplus for the greater good, to help rebalance the EU’s lopsided economy.

“There is a strong argument that Germany is not investing sufficiently in its future. Things like transport infrastructure, communication and the Energiewende [the energy transition],” explains Lallement.

There is also the question of the recent massive influx of migrants. Their contribution to the country’s prosperity could well depend on how much the government is willing to invest in their potential.

Despite this wave of new arrivals, Germany faces the prospect of demographic decline, which will likely hinder economic growth over the long term. Add to this the consequences a protectionist wave led by the US could have for German industry, and the country’s future looks uncertain.

Nevertheless, it is far from too late for Germany to use its current position of strength to prepare for these eventualities. As Lallement concludes in his paper, despite a wariness regarding discretionary fiscal measures, the German Council of Economic Experts (Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung) has in the recent past advocated for nothing less.